Longitude by Dava Sobel is the very readable

tale of John Harrison's astonishing, life-long quest to build

timepieces that were suitable for maritime use in the determination of longitude.

Longitude by Dava Sobel is the very readable

tale of John Harrison's astonishing, life-long quest to build

timepieces that were suitable for maritime use in the determination of longitude.Self-educated and living far from the madding crowd in Barrow, his first clocks were largely wooden. Harrison's earliest surviving clock movement, dated 1713, can be found at the The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers of London.

He first set his mind to the challenge of maritime timekeeping in 1727. The Board of Longitude had been established in Britain by Act of Parliament and offered a prize of ₤20,000 for a method that could determine longitude within 30 nautical miles (56 km).

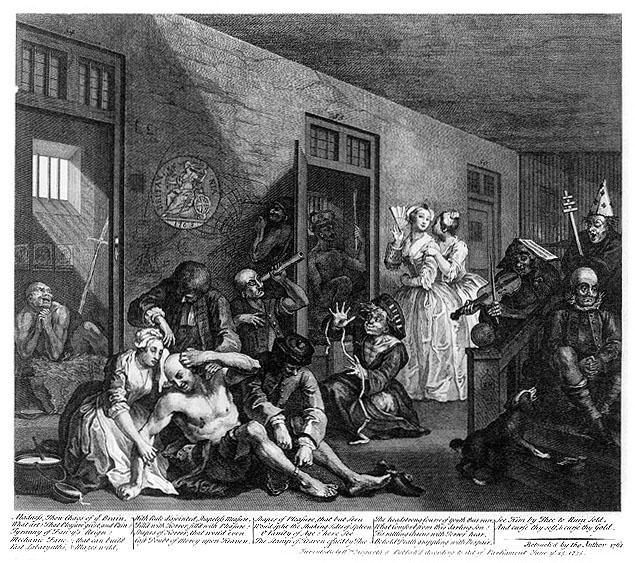

The problem of longitude had long plagued sailors, sending many crashing to their deaths on unexpected landfall, or dying from thirst and scurvy lost at sea. It was the subject of much public discourse, as global warming is for example today. It even makes a cameo in William Hogarth's engravings of A Rake's Progress (note a man scribbling a dim-witted solution to the longitude problem on the wall, centre).

The method for determining longitude by comparing local time with the time at a known origin relies on very accurate time keeping. Beyond the capabilities of clocks of the age, even on land. At sea, the combined effects of motion, temperature and gravity made the approach seemingly impossible.

Despite support from the Royal Society, the Board of Longitude was well stacked with those who favoured an astronomical approach, relying on measurements of the passage of the moon. Nevil Maskelyne proved to be Harrison's arch-nemesis and main proponent of the lunar distance method. Although the chronometer eventually won over seafarers (and King George III) through its simplicity and reliability, Nevil's Nautical Almanac became his enduring legacy and is still published today (minus the lunar distance tables).

After producing five timepieces (H-1 through H5), John Harrison was finally recognised in 1773 by Parliament to have proven his claim, although he was never to officially be awarded the full prize by the recalcitrant Board of Longitude. The National Maritime Museum of Britain has a comprehensive time Gallery which features H-1 to H-4. H-5 is at The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers of London.

It was Harrison's successors, like Thomas Earnshaw, to fully commercialise the maritime chronometer. Yet they all owe their successs to the many innovations that Harrison pioneered.

The machine used for measuring time at sea is here named a chronometer, [as] so valuable a machine deserves to be known by a name instead of a definition.

-ALEXANDER DALRYMPLE in his pamphlet 'Some Notes useful to those who have Chronometers at Sea'