AISLE: The End of Zero-Days?

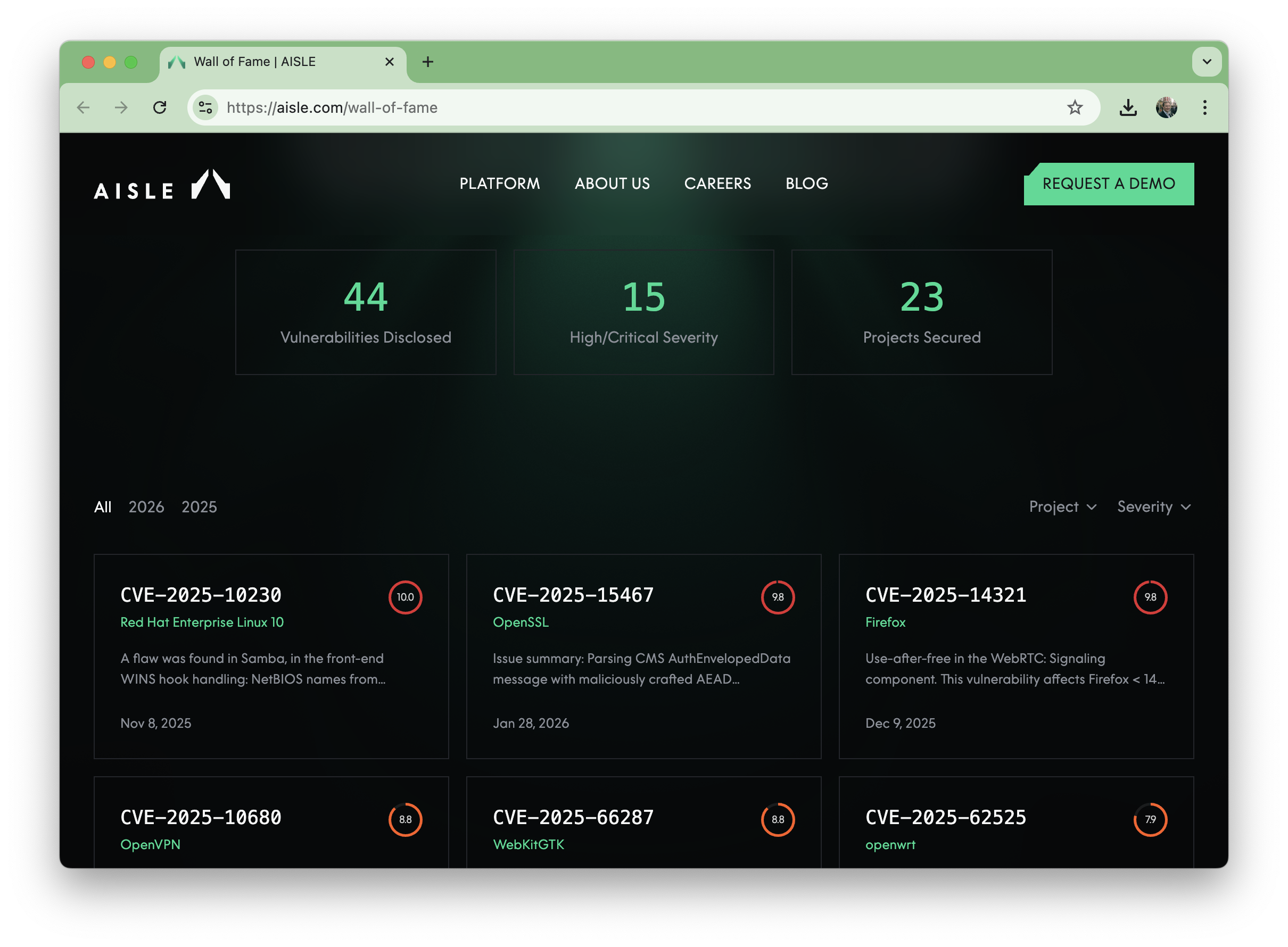

AISLE have been developing a complete AI workflow for deep cybersecurity discovery and remediation,

and if their Wall of Fame is any indicator of potential,

they may prove to be one of the most transformative companies to emerge from the AI bubble.

I must admit to being a little jaded. Where are all the AI startups delivering meaningful breakthroughs?

We were sold a vision of AI curing cancer, ending the climate crisis, and eliminating poverty.

Instead, much of the commercial narrative seems to have fixated on workforce reduction and generating a tidal wave of AI slop, along with a huge power bill.

So I wasn’t expecting to be impressed when I heard about AISLE on Security Now #1063.

But I was.

It’s 2026, and we still treat vulnerabilities as “Normal”

Since computing’s original sin of mixing code and data, security has been a cat-and-mouse game. We’ve made enormous advances in system and network security, yet we still accept one assumption as inevitable:

There is no such thing as bug-free code.

As developers, we follow secure coding practices. We run static analysis. We adopt DevSecOps pipelines. And still, vulnerabilities ship.

Our experience with AI coding tools such as Claude Code and GitHub Copilot is mixed. They fix some bugs, hallucinate others, chase red herrings, and lack a true closed-loop workflow for discovering and eliminating security flaws.

What is AISLE doing differently?

AISLE’s ambition is simple and radical: software released with zero known security vulnerabilities. Where software is assured by AISLE to be free from security vulnerabilities before it is released.

The company emerged from stealth in October 2025. In the absence of reliable cybersecurity benchmarks, they targeted live, heavily audited open-source projects including:

- OpenSSL

- curl

- Firefox

- Linux

- OpenVPN

The results have been remarkable:

- OpenSSL security patch of 2026-01-27 addressed 12 new zero-day vulnerabilities - all discovered and remediated by AISLE

- curl 8.18.0 released January 8, 2026, AISLE was responsible for 3 of the 6 CVEs

If accurate, that’s not incremental improvement. That’s industrialized vulnerability discovery and remediation.

AISLE appears to be succeeding not by building a better autocomplete engine, but by creating a full AI-driven workflow dedicated to one problem space.

Is “Zero Vulnerabilities” Realistic?

For many of us versed in the “old ways”, this sounds too good to be true! And to be sure, if software is free from security vulnerabilities, that is not the end of security issues.

Even perfect code doesn’t eliminate phishing or credential theft. Humans will always remain part of the attack surface.

But removing exploitable software flaws changes the economics of cybercrime dramatically. No zero-days means fewer catastrophic breaches.

Another AI Unicorn?

AISLE emerged from stealth backed by angel investors. No major institutional round or valuation has been disclosed yet.

But if their trajectory continues, they may become something rare: not the first AI unicorn, but possibly the first AI unicorn to actually do something significantly good for the world!

What Happens Next?

The obvious path is integration into CI/CD pipelines with a security assurance as a subscription service. One can request a demo, but I’ve not yet seen any pricing.

Longer term? Pure speculation, but I would not be surprised to see a rapid exit and acquisition. My bet would be Microsoft:

- to use internally:

- A world without Windows security patches, because there are no vulnerabilities to fix!

- to integrate with Microsoft-owned GitHub as a value-added service:

- A perfect pairing or upgrade to the existing Dependabot and Code Scanning services

- A must for enterprise clients, while ensuring the open-source supply chain that so many companies rely on is kept free from issues

If AISLE can assure software security before release, “reasonable industry practice” changes. Releasing vulnerable code may eventually be considered negligent under the law, with the old “no liability” boiler plate in license agreements challenged in court. Be prepared to defend why you are not using a service like AISLE!

References:

- aisle.com

- AI found 12 of 12 OpenSSL zero-days (while curl cancelled its bug bounty)

- Security Now Episode #1063

read more and comment..

AI in the Call Centre

AI is decimating call centres, but two can play at that game!

Inspired by true events😂

read more and comment..

Tyranny of the Urgent

The Agile Embedded Podcast is as thought-provoking as ever with their take on the Tyranny of the Urgent. The discussion focused very much on how the agile mantra of creating immediate customer value can lead a team astray, but it made me think of all the other ways I’ve seen and experienced the “Tyranny of the Urgent” over the years.

Three thoughts came to mind:

- We’re Not Being Honest about Impact and Urgency

- We are ignoring the Full Feature Lifecycle

- When Things are Always Urgent, it may just be a Capacity Problem

Tyranny of the Urgent: An anti-pattern where short-term urgent demands systematically override long-term important work, causing reactive behavior and worsening future urgency.

Problem 1. We’re Not Being Honest about Impact and Urgency

Task priority should be a factor of both Impact and Urgency. This is as true in agile environments as elsewhere. It’s a common prioritisation technique that appears in many guises (in project management, ITIL support, Eisenhower matrix, PICK Charts) but as a concept is trivially simple.

No matter how a team calculates priority, it is very sensitive to the fact that both impact and priority are hard to quantify and extremely subjective.

In reality, I’ve often had to deal with, let’s say “misleading”, assessments of impact or urgency. For example:

- the product owner claiming a feature is critical based on an imaginary concept of the customer

- i.e. trust me, I know what the customer needs without any data or actual customer input to back it up

- it can be a symptom of a team that is far past their initial requirements efforts and is now coasting.

- Solutions?

- without being rude about it, find a way to reset expectations around validating requirements before they are accepted for development.

- Discuss the “definition of done” for a story/requirement itself.

- May need a jolt to re-engage meaningfully with the customer group, perhaps with a new round of focus group, customer surveys, or customer visits.

- a sales person claiming features are deal-breakers for a new customer and must be urgently delivered to close the sale

- sometimes this may be true, but in many cases I’ve discovered it’s not (most painfully, after the fact)

- it may be “lazy sales”: passing the buck to development rather than do the hard work of selling the solution as-is and overcoming customer objections

- but it can also be a skills gap: sales or pre-sales don’t know the solution well enough or have the requirements analysis skills to help best assess the solution fit and gaps for the customer

- Solutions?

- the main way I found to battle this is greater involvement of development in the pre-sales process, proposal design and review.

- it may point to a lack of training on your product with the sales, pre-sales, or customer care teams

- whatever the C-suite says this week is the most urgent and important thing to work on

- i.e. if you have the authority, you can bypass whatever process is in place for product management

- This can be tough, because at the end of the day “the boss is always right”!!

- I’ve mainly seen this in places where senior management either don’t understand the processes used to manage product development, or they don’t trust it to deliver the necessary results

- Solutions?

- invest time in building the stakeholder relationships and educating them on how development works.

- nothing beats a good track record to build trust.

- if execs only hear about development when things go wrong, they’ll think that’s the norm

- make sure to provide regular updates that include all the good news about the process working correctly

Problem 2. We are ignoring the Full Feature Lifecycle

The podcast did touch on the Three Horizons model for ensuring there’s always an innovation pipeline, but on a smaller scale I’ve seen insufficient attention paid to appropriately balancing effort across the full lifecycle of features.

The most common anti-pattern I’m sure we’ve all seen is all effort consumed on new feature development, and only allowing for some effort to be clawed back to fix bugs. The team ignores the important work of taking features from good to great, and never gets around to retiring features that no longer add value.

I’m my own practice I’ve found “4Rs Feature Lifecycle Analysis” a very useful diagnostic to combat this. In essence, all stories get classified as belonging to one of the four stages of a feature lifecycle:

- Stage 1, Reveal: new feature development

- Stage 2, Refine: improving a feature

- Stage 3, Rectify: fixing bugs, CVEs, updating dependencies etc

- Stage 4, Retire: removing the feature when it no longer has sufficient value

Looking at where effort is bucketed makes it very clear if the product management process is delivering a pipeline of work that matches the maturity of the product. i.e.:

- during initial product development, one expects most effort to go into new feature development

- after launch

- if one is not seeing a shift towards refinement, it may indicate we are stuck in “new feature mode” and are not taking the time to improve the “v1” features already launched

- and if we see rectification starting to swamp feature development, it may indicate systemic quality issues

- in very mature products, we’d expect to see effort largely shift to rectification and ideally an uptick in retirement effort

If we are using agile software development process, isn’t Feature Lifecycle Analysis redundant? A well-balanced and high-performing team should be able to find the optimal balance by trusting the process:

- customer/business requirements rule, and are represented in the team through a product owner or even an onsite customer

- we prioritise work for each iteration as a team, balancing customer/business requirements with other things that the team knows are important in order to meet customer expectations (like performance)

- we keep our iterations short and continuously deliver working software, so even if we get things wrong we can course-correct in short order

That is of course the ideal. But we operate in the real world, and many things can upset the balance. For example:

- Urgency Trumps Impact

- It’s easy to find a queue of people ready to argue for the latest urgent requirement, but there’s no-one around to champion the more impactful stuff that hasn’t also been called out as urgent. Result? Six months later, we’ve delivered all the urgent things, but 90% of the potential impact (“value”) is still on the table.

- The New Shiny

- The new shiny trumps last week’s idea. This can be a problem in startups where the founder/ideas person is also the product owner. Excellent at generating new ideas, but no time or ability to follow-through. So the team leaves a trail of half-baked implementations but never seems to achieve anything great.

- Uninspired Leadership

- The team is looking for insight and vision to drive priorities but just hears “meh”. So the results are naturally also meh.

- Unreal Priorities

- A product owner who is (consciously or not) skewing priorities towards a certain theme or faction over all others, like one particularly vocal customer. Or perhaps lacking real customer insight, priorities are out of touch with reality.

- Weak Team

- A weak development team that’s not able to put up a convincing case for something they believe is important.

- Domineering Team

- Conversely, a development team that is too strong and always manages to spin the product owner to their way of thinking.

- Group Think

- Although we use a strict planning game to prioritize stories, the team is suffering from “group think” and priorities end up skewed to one point of view.

- ScrumMaster At Sea

- A scrum master that doesn’t recognise there’s an issue of balance until it is too late, or is running out of tricks to help the team fix it.

Feature Lifecycle Analysis is really just a diagnostic that can present in a picture what may otherwise just be a gut-feeling that something is not quite right.

Problem 3. When Things are Always Urgent, it may just be a Capacity Problem

We refined our scope to death, optimised all our processes, fine-tuned our tools, made all the improvements surfaced by our retrospectives, ensured all our people are well trained and working at their best… BUT we are still consistently failing to meet expectations for feature delivery.

We may just need to admit we have a fundamental capacity issue, and no amount of clever scheduling can plan our way out of the hole. Are we trying to do the work of an 8 person team with a team of 3?

If that’s the case, frankly it’s time for leaders to step up and either:

- reset expectations with stakeholders

- or make the case for investing in greater capacity

Listen to the Podcast

Yes, it is an old episode from 2023 but no less relevant for the fact. I’m busily catching up on back episodes;-)

read more and comment..

After Pivotal Tracker

When Broadcom/VMware announced it was shutting down Pivotal Tracker effective April 30, 2025, it signalled the end of an era. And had me scrambling to find a replacement!

TLDR: I moved to BardTracker and LiteTracker.

Pivotal Tracker (PT) was created in 2008 by Pivotal Labs as an internal project management tool based on agile principles. It was later released as a commercial product but eventually became part of VMware Tanzu Labs after its parent company, Pivotal Software, was acquired by VMware in 2019. Following VMware’s acquisition by Broadcom, Tanzu Labs was shut down in early 2025, and PT was retired in April 2025.

- 2008: Pivotal Labs develops Pivotal Tracker for internal use.

- 2012: The company, now known as Pivotal Software, is formed.

- 2019: Pivotal Labs is acquired by VMware and renamed VMware Tanzu Labs.

- 2023: VMware is acquired by Broadcom.

- 2025: Tanzu Labs is shut down in January, and Pivotal Tracker is retired in April.

I was first introduced to PT while working alongside Pivotal Labs consultants on Rails projects in 2008/2009. For me, it represented the same simplicity and effectiveness in planning that Ruby and Rails brought to development itself.

I was converted, and while I’ve had to use many other systems before and since (Jira, Trello, bugzilla, even FogBugz and others), nothing has helped me to just get things done so well, without adding undue cost or complexity.

So like many others, I was in a desperate search for alternatives in 2024/2025, and even considered writing my own if I couldn’t find anything suitable. This was especially true as I’d long since internalised PT and used it for getting things done in all aspects of life.

The good news: I found answers and was able to smoothly migrate all my ongoing PT activity to alternatives. Here’s a quick summary of what I ended up using

BardTracker

I’ve moved all my personal and small project activity to BardTracker. It was specifically developed by Bot and Rose Design (BARD) as a PT replacement for their own consulting work, and they now offer it as a service for others.

What I like:

- it has a nice free tier - perfect, especially for personal GTD/TODO lists

- GitHub integration

- looks and works similarly enough to PT

- is really well supported. I’ve had very fast response to any issues or features requests I’ve raised.

- it’s backed by an operating concern, so should have some longevity

To consider:

- the UI is not identical to PT - there are differences, some of which may be significant for you

- no API access (yet)

- no mobile app, but mobile responsive view is quite OK

LiteTracker

It really is the most complete and “identical” PT replacement that has made it into full operation. If you want something exactly like PT, this is the best I’ve found. As it has no free tier, I haven’t adopted it for personal projects, but it would be my first choice the next time I start a new project with a larger team.

What I like:

- every feature you ever liked from PT is here

- it really is pretty much identical

- after the initial focus on migrating from PT, they’ve continued to add migrations from other popular planning tools

- now has a mobile app

To consider:

- the developer API is still a work-in-progress

- only paid tiers

Other Solutions

Quick notes on some of the others I considered when looking for a PT replacement.

Direct PT Replacements

- Lanes

The secret superpower of the most productive teams.

- I applied for the beta but never heard back

- appears they have now launched with something that looks very much like PT.

- Doesn’t mention having any integrations or API

- Have not tried it though

- Pivotal Replacement

- Never made it live (yet)

- Storytime

- Began a discussion on PT replacements

- Not a solution itself

Other Planning Solutions

For a while I did consider whether I really wanted a PT replacement, or would be better served by something different.

These never aimed to replace PT directly, and none offered any migration support from PT. It is not an exhaustive list of tools by any stretch, and I excluded all the more traditional project management tools.

- ClickUp

- Didn’t like it.

- Although has a free option, the task management is overly cluttered. Does not help keep things organised.

- Todoist

“Use Todoist for free forever or upgrade to unlock our most powerful features for work and collaboration”

- Lacks GitHub integration

- Had no PT migration solution

- Linear

“a purpose-built tool for planning and building products”

- Has a free tier with GitHub integration

- Had no PT migration solution

- Works very differently than PT

- Wasn’t the immediate replacement I was looking for but has me interested to try at some point

- Plane

“Plane is the modern project management platform—bringing projects, knowledge, and agents together in one place.”

- Asana

- the grand-daddy of “social networking, but for work”

- has a free tier, with integrations

- Aha!

- expensive

- Wrike

- more for enterprise planning

- limited free tier

- monday.com

- The Asana killer

- At the time, not particularly geared for development

- But I note that has now changed with monday dev

- Trello

- Never really liked it

- Works for initial brainstorming, but once things grow to real-world levels of complexity, things get easily lost

read more and comment..